Tweet Tweet Upon its eventual release, the Aaton Penelope Delta just might be the most innovative digital cinema camera on the market. The Delta features 14 stops of latitude, onboard 3.5K RAW recording in CinemaDNG (with simultaneous proxy recording ability), the world’s first optical viewfinder for a full-res internally-recording camera, an ISO 800 base sensitivity, a mechanical shutter able to reduce that sensitivity by 3 full f-stops, a revolutionary sensor package that simply boggles the mind, and all within a quiet, operator-friendly body. This machine means business — and it’s not going to be cheap, either — but the specs and design plainly speak for themselves. Read on for the full details. Here is Aaton’s founder Jean-Pierre Beauviala on the camera at this year’s IBC: IBC 2012 - Aaton from Film Cyfrowy on Vimeo.

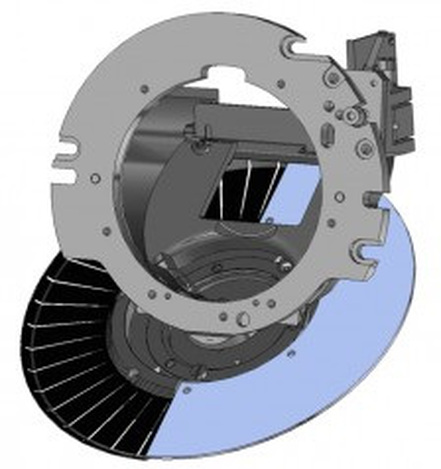

The specs list is really only the tip of the ice-berg, though. Some of the other unique design elements that make the Penelope Delta so note-worthy require a bit more in-depth explanation.  The Shutter The major side-effect of the low-light revolution is, well, our imaging chips naturally being really sensitive to light. This can become a problem in well-lit conditions, traditionally necessitating the use of neutral density filters. A problem we discuss a lot less is the infrared pollution that regular ND filters can create. Aaton’s solution to this problem is ingenious because it almost literally reexamines and reinvents the wheel, so to speak: the shutter. In addition to allowing you full mechanical control over shutter-angle, the Penelope Delta allows you to switch from a traditional half-moon spinning mirror to another set of blades which transmit exposure through many tiny slits. This reduces the ISO 650/800 sensitivity of the shutter down to about ISO 80/100, all mechanically/optically, and without affecting the shutter angle itself. A render of this design, courtesy of Aaton, is pictured to the right. This method also circumvents the loss of dynamic range that occurs with the attenuation employed by DSLRs at sub-base ISOs. The Sensor The sensor itself is another, well, marvel, really. A number of things make the Delta’s imager special, not the least of which is its Dalsa origins (anybody?) and the fact that it’s a CCD — an acronym we haven’t heard attached to new cinema camera descriptions for far too long in my opinion. The way things have been going for a while now seems to dictate that CMOS sensors are less expensive and, in terms of bang-for-buck, more potentially light-sensitive than would be their CCD counterparts. To be honest, I really never thought I’d have a chance to say this — but we now have a 3K+ Super35 sized ISO 800 CCD at the head of a motion picture camera. The reason Aaton chose a CCD over CMOS has to do with another thing we don’t usually talk about — photosite fill-factor. As John Brawley explains in a great post on the camera, CCDs have a greater pixel-fill potential than CMOS sensors do, because less of a CCD’s surface area must be dedicated to transfer circuity rather than light-capturing elements. This means the Penelope Delta will possess smaller “gaps” in the image it gathers, as its sensor has a 90% fill-factor versus the 75% commonly found in CMOSs. This will help to eliminate aliasing potential, for one, as well as produce a more all-around “full” image (visual explanation of sensor fill-factor from Dalsa in Links below). Something even more space-age about the Delta’s sensor, though, is an option which allows the sensor to actually move in place. This capability oscillates the imager by a half-pixel offset each frame, randomizing the noise structure of the image. Fixed noise structure is a difficult problem to bypass in the digital world, but it seems as though Aaton has done so to a point never before achieved. Moreover, Aaton claims that the resolution created by this sensor movement actually increases the effective spatial resolution of the imagery over time. Though any given single frame will resolve whatever a debayered 3.5K image equates to, in motion the consecutive frames combine to virtually resolve an estimated 7K before debayering. That’s right — the Penelope Delta’s sensor can resolve 7K RAW through a method of time-travel (not really but you can understand what I mean). The Results After all of this mind-bending innovation, what do the images created by the camera actually look like? Film and Digital Times got a chance to check out some test clips shot by Caroline Champetier, AFC, and had this to say about the footage: Racing from IBC hall 11 to Marquise technologies in hall 7, we looked at the dailies. Filmic and gorgeous. An available-light scene in a cafe held noiseless detail in deep dark shadows under the chair (below, left) while highlights in the silver espresso machine did not burn out (right). Apologies to Caroline–my graded jpeg below doesn’t do full justice to the original DNG file. Here’s the graded jpeg in question (courtesy Jon Fauer, FDT): You may access the CinemaDNG clip this still is from and others from the links below.

As mentioned earlier, when this camera comes out — and there doesn’t seem to be any definitive release dates thus far, though John Brawley estimates that five working prototypes will ship in December — it’s not going to sell for pocket-change. Mr. Brawley’s post says the target price will be around 90,000 Euros, which is about $120,000. That’s more than a little outside the realm of short-term ownership for me, but I’ll be pleased if I have the opportunity to work with the Penelope Delta on a rental basis before I turn 71 years old. Are you guys as excited about the technologies at work here as I am? Do you think the Penelope Delta will be able to cut a sizeable share out of the RAW digital cinema market once it comes out? Links:

1 Comment

|

KimataDP | Director | Editor ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed